In Times of Crisis, a Good President Should Be a Good Listener

- Justin Dynia

- Nov 22, 2021

- 6 min read

Updated: Mar 28, 2022

Biden’s record on taking experts’ advice has been a mixed-bag. He can learn from how Kennedy avoided nuclear war.

From battling the global threats of the pandemic and climate change to ending America’s longest war, President Biden has made demanding judgment calls during his short time in the Oval Office.

A good leader can reach a consensus even in the greatest of crises. Biden claims to make listening to the experts a central tenet of his leadership strategy. He consciously abandons the strongman, macho style of leadership of other presidents in the Oval Office. The style defined the pandemic response of former President Donald Trump, including his unrelenting denial of the severity of the pandemic and difficult episode battling the virus himself.

Although Biden’s track record on the pandemic confirms that commitment, his decisions in Afghanistan reveal abject failures to heed expert advice. One of his predecessors, President John F. Kennedy, struck a delicate balance between taking the advice of experts around him and bringing them into agreement when taking a different course of action. For Biden to effectively deal with future crises, he will have to develop a strategy to get the best out of his support system and create consensus.

Thirteen Days

President Kennedy meets with members of the Executive Committee of the National Security Council (EXCOMM) regarding the crisis in Cuba. Photo Courtesy: JFK Library

When the country found itself on the brink of nuclear war, President Kennedy did more than take action: he listened. For thirteen harrowing days in October 1962, America looked down the silo of a missile rather than the barrel of a gun.

At the height of the Cold War, an American U-2 plane photographed the presence of nuclear missile sites being built by the Soviet Union in Cuba. Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev’s decision to place missiles just 90 miles away from American soil carried the potential to create massive conflict.

All eyes turned to the commander-in-chief when the news broke to the general public. At age 45, John F. Kennedy earned the right to call himself an accomplished Harvard scholar, Purple-Heart decorated Navyman, Congressman, and Senator all before winning the presidency.

Immediately after being briefed by the CIA on the morning of October 15, President Kennedy officially commissioned the Executive Committee of the National Security Council (ExComm). T

he members of this committee included trusted experts, officials, friends, and others who would advise him throughout the crisis—notably his brother Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, Secretary of State Dean Rusk, National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy, and Statesman Dean Acheson. Kennedy also decided to secretly record these meetings, documenting how each phase of the crisis unfolded and etching them into the historical record.

Kennedy possessed the highest authority in the room and could have made any decision he felt best. As pressure mounted and the clock ticked, he wanted all of his options on the table.

Linguistic analysis of the ExComm meetings revealed that questions constituted 62% of Kennedy’s interventions on the meeting on October 16. He asked questions about grand strategy and fine details, attempting to facilitate productive conversation and extract information out of his advisers rather than impose his own ideas.

On October 19, Kennedy convened a meeting with the Joint Chiefs of Staff who proposed a comprehensive assault on the missile sites and ensuing United States ground invasion. Kennedy countered with a proposal to set up a blockade around Cuba, an action that did not actively address the missiles in place.

The next day he set up these advisers and other members of ExComms into two groups. The “hawks” pressed for military action and the “doves” supported a blockade. Kennedy heard out both sides and decided to move forward with a blockade as the preferred option. His motion was adopted by all the advisers despite their initial disagreements. Drawing upon the decades of expertise from trusted authorities with a variety of perspectives, Kennedy closed his mouth and opened his ears before taking decisive action that had massive ramifications.

At 6:00 p.m. on October 26, a solution seemed imminent when President Kennedy received an emotional letter from Khrushchev proposing a favorable solution to end the crisis: all Soviet missiles in Cuba would be removed if the United States pledged to end the blockade and not invade Cuba. Kennedy and ExComm resolved to reconvene the next morning to draft and send a response. They felt hopeful for the first time in ten days.

Another letter from Khrushchev came the next morning and shattered that hope. In the impersonal and aggressive letter, Khrushchev admonished the United States for inflaming tensions. He demanded they pledge to end the blockade, stay out of Cuba, and remove the Jupiter missiles in Turkey. Khrushchev also implicated Turkey and Berlin as sites for possible retaliation if the United States attempted to attack Cuba.

The opportunity to launch a preemptive strike could no longer occur with NATO allies at risk. Kennedy had two options. He could finalize a letter written by his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, responding to the initial favorable terms, or send a draft written by the State Department giving a defiant denial of the latest terms. After a full day of painstaking deliberations, President Kennedy decided to finalize Robert’s letter and send it immediately to Chairman Khrushchev.

The letter had one crucial addendum. President Kennedy sent his brother to meet with Soviet Ambassador Dobrynin to express the United States’ wishes to privately include removing the outdated Jupiter missiles in the deal. Making this move public would have caused significant complications with global allies. At 10:00 a.m. on Sunday, October 28, a morning many thought could be their last, the White House received word from the Soviets that the missiles in Cuba would be removed.

The United States agreed to end the blockade, stay out of Cuba, and remove the Jupiter missiles within six months, while the Soviet Union agreed to remove all missiles and other armaments under UN inspection. Nuclear war had been averted.

Missiles to Microbes

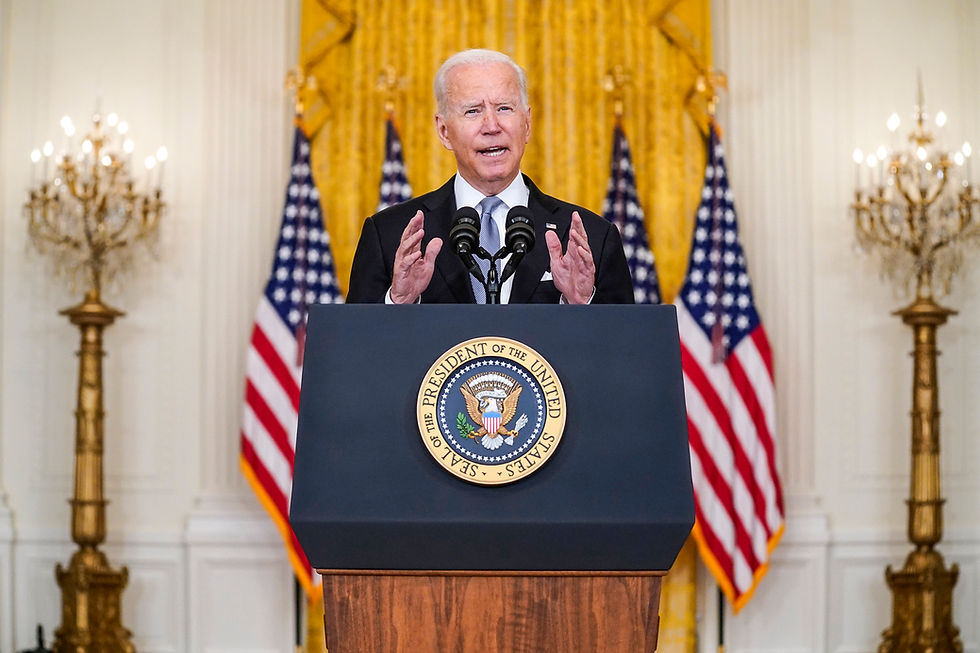

President Biden delivers remarks from the White House on Aug. 16 on the military situation in Afghanistan. Photo Courtesy: Evan Vucci/Associated Press

President Biden took the helm amidst a global fight of microbes rather than missiles. The Covid-19 pandemic has already claimed the lives of 736,000 Americans and counting. Vaccinations have stalled for weeks despite over half of the population having received at least one dose.

Less than two weeks after his election in November, then President-elect Biden and then Vice President-elect Kamala Harris met virtually with a bipartisan group of governors to discuss a cohesive strategy for battling the pandemic. This attitude has continued into his administration and shaped his strategy for uniting states behind a strong vaccine rollout and continued recovery efforts.

Biden has placed trust and a willingness to listen to the medical experts who both call and give the shots. His close relationship with National Institute of Allergy and Disease Director Dr. Anthony Fauci is well-documented. When Dr. Fauci talks, and when the CDC updates their never-ending flurry of new guidelines and safety measures, Biden listens and encourages others to do the same. That genuine desire to learn from others he outranks is a valuable tool when confronting a generational challenge.

Yet when the situation came down to leaving Afghanistan, Biden ignored the advice of the experts. Advisers at the Pentagon told him explicitly to stop the full withdrawal of troops. Refugee advocates pleaded that he would be making an irreversible mistake and would spawn a massive refugee crisis.

Instead of bringing his advisers to a consensus as Kennedy did, he leapt headstrong into a course of action that many felt had drastic consequences. The fall of Kabul on August 15 has since become an undeniable day of American geopolitical embarrassment and another failed experiment of nation building abroad.

Biden has demonstrated both a willingness to listen and a resolve to make bold decisions he firmly holds to be true. The results have been a decidedly mixed-bag. To whom he listens will remain one of the larger questions in his overall policies. From pleasing the experts to appeasing different factions within his own party, Biden has a plethora of voices in his ear making requests and demands.

President Biden now faces the task of being a good listener outside the public eye and a strong leader in the spotlight.

Comments